What is Integrated Care?

While there is not a nationally recognized definition of integrated care, our organization uses the term to describe efforts to provide healthcare services that bring together all of the components that make humans healthy. Given that the promotion of health involves a variety of factors (psychological, biological, social, communal, economic), integrated care can and should look different based on the setting of the healthcare delivery and the participants. Many of our members are centered in primary care, a central location in the US healthcare delivery system. However, we also have members working to integrate care in other settings such as emergency departments, hospitals, mental health centers and community settings such as social service agencies. We have members who are part of the payer system (insurance companies) working to integrate care at the reimbursement level.

We also have members in universities promoting training and research for professionals (and peer support) to learn to work in concert with one another. In the end, integrated care results in professionals working from a unified framework, often side-by-side (whether physically or through technology), incorporating the whole patient experience (patient, family and community as equal partners). The result should be care that is efficient, cost-effective, resulting in positive health outcomes and is meaningful and fulfilling to the workers in the healthcare delivery system.

One way to think about integrated care is to consider the models, clinical pathways and perspectives that make up these efforts to bring together parts of the healthcare delivery system that traditionally work in silos.

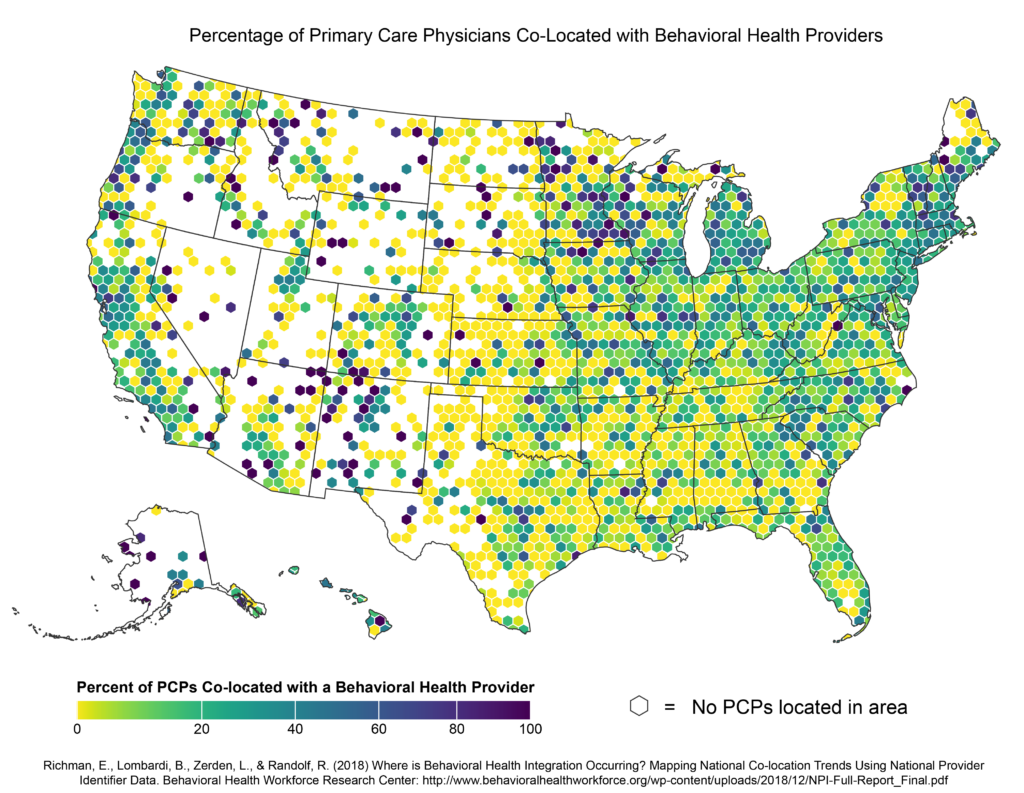

There is a paucity of research identifying exactly how many practices across the United States provide integrated care, however the above graphic provides a baseline of sorts in that it depicts geographic colocation (view whole article here). While colocation does not guarantee that providers are working together in meaningful ways, this research is a stepping stone to research that could help us understand the proliferation of integrated care. Of note the researchers point out in their narrative that rural areas are clearly disadvantaged in the possibility of integrated care provision occurring.

Models

Models are delivery strategies that prescribe specific ways in which professionals will work together to provide healthcare services. The preponderance of work in integrated care models centers on primary care with two main models of integrating behavioral and medical care. These models are not mutually exclusive. Many of our members run various models in their practice sites.

Primary Care Behavioral Health, PCBH, is a model of care that seeks to optimize access to behavioral health support within the primary care environment across all possible patient presentations. In this model behavioral health professionals, often called Behavioral Health Consultants (BHC), work alongside medical providers in real-time. They are often called into exam rooms to work with patients in what is called a “warm hand-off” where the patient sees the physician first and then sees the BHC. On follow-up visits the patient may see both providers or only one of the pair depending on the situation and need. BHCs can provide support for mental health concerns such as depression, anxiety or ADHD as well as physical health concerns such as management of diabetes, hypertension or sleep issues to name a few. One of the central goals of the PCBH model is to improve access to care (referral out of primary care to specialists has been shown to be difficult) while supporting the interventions of the medical care team.

For more on the PCBH model see our PCBH Special Interest Group page.

The Collaborative Care Model, CoCM, seeks to impact the clinical outcomes of patients who present with depression in primary care. In this model a consulting psychiatrist and care manager is added to the care team to manage a registry (list) of patients from a practice who have been screened as needing support for depression using the PHQ-9 (a standard depression screening tool). The consulting psychiatrist provides support primarily to medical providers to ensure that they are providing evidence-based prescribing of antidepressant medications, but they may also see patients for a short course of treatment or as needed. The care manager may meet briefly with patients in person or by phone for behavioral intervention and keeps track of care using the registry to make sure that patients are improving in a timely fashion. Key to this model is the tracking of outcomes through the repeated use of the PHQ-9. More recently the collaborative care model has been piloted for use beyond depression to include other chronic conditions that can co-occur with depression such as cardiac conditions and diabetes. Evidence for the clinical effectiveness of the collaborative care model exists here.

The introduction of team-based care to non-integrated settings can raise ethical concerns for professionals working across guild groups. For example, psychologists have a different ethics code and different ethics training than physicians – so how do they work out ethical considerations when working with the same patient/family? This document (linked below), produced by an independent working group provides an example of the ways in which ethical issues need some translation in integrated care settings and also provides a bibliography that is useful for reviewing the emerging standards for ethics in this area. Note that the document represents the views of the authors and not necessarily their respective institutions, nor CFHA (though many CFHA members participated). It was produced to help guide the American Psychological Association committee charged with revising their ethics code in 2019-2020.

Summary of Considerations for APA Ethical Standards Revisions

Clinical Pathways

Clinical pathways are algorithms used to guide care to ensure that persons with specific conditions receive monitored, timely care. Here we highlight two common clinical pathways.

SBIRT is a clinical pathway whose aim is to identify and provide brief intervention to patients with substance abuse conditions. In this model a behavioral health professional, sometimes a Behavioral Health Care, BHC, is co-located with the medical team to assist patients real-time who screen positive on standardized screening tools such as the AUDIT and/or DAST. The behavioral health professional is trained in motivational interviewing strategies (as are other members of the medical team) to engage patients at the mild to moderate range of difficulty. Patients with severe substance abuse concerns are referred out to specialty providers with assistance from the behavioral health professional. The SBIRT pathway has also been applied to other conditions such as nicotine addiction. Evidence for the clinical efficacy of SBIRT exists here.

MAT is a clinical pathway designed to improve the treatment of opioid addiction in primary care. MAT involves at a minimum a primary care provider trained and licensed to provide medication to help patients reduce and/or eliminate their dependence on opioids. However, in many applications a behavioral health professional, such as a BHC or care manager is assigned to work with suboxone certified providers to engage patients with treatment support including relapse prevention support and motivational interviewing. MAT is an evolving area with great variety of implementation depending on the available resources in a clinic.

Perspectives

Perspectives are approaches or frameworks that guide and feed integrated care efforts. They serve as the source of the guiding principles that drive the training of professionals in integrated care and result in the evolution of specific healthcare delivery models. Below are some of the perspectives that drive the integrated care movement.

You may have noticed the term “family” in our name. This is because one of the guiding principles of our definition of integrated care is that a patient’s family (and community) are central to the promotion of health. Medical Family Therapy, MFT, is a discipline that for over 30 years has promoted the centrality of including the family in care delivery. MFT as a perspective, reminds all professionals in healthcare of the benefits of and need to include the patient’s loved ones in the promotion of health and amelioration of disease. Examples where this approach has been used include childhood obesity interventions, cancer care and chronic disease management.

The Patient-Centered Medical Home, PCMH, movement is an effort to improve the efficiency and outcomes of primary care clinics by promoting team-based care. Key to this movement is the coordination of team members, especially in the provision of care for chronic conditions such as diabetes and depression. For this reason certification involves efforts to screen patients with key conditions, track outcomes, utilize electronic health records for documentation and communication and work proactively with specialty providers. PCMH efforts often coincide with clinic-wide efforts to integrated mental health services because of the significant overlap in quality improvement processes and goals of PCMH and integrated care.

The research behind Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and efforts to promote trauma informed care are central perspectives driving the need for integrated care given how closely tied medical conditions are with traumatic experiences. Integrated care efforts often include screening for trauma in medical settings and efforts to provide increased access to behavioral health support in the medical setting to increase patient engagement with care.

Increasingly the impact of social aspects of human functioning are recognized as contributing to the promotion of health to a greater degree than the health care delivery system itself. In other words, being healthy is not primarily about going to see your doctor. However, health systems can enable improved health by identifying ways to partner with the communities they serve by identifying social aspects, such as inadequate supply of healthy foods, poor housing conditions or other community characteristics that impede optimal functioning. In health settings this often takes the form of screening for social determinants and providing assistance to patients who have areas of their life which impede their ability to care for themselves effectively.

Personnel

Who are the professionals and others involved in the provision of integrated care. The short answer is that our goal is that all healthcare professionals operate from an integrated care framework (biopsychosocial). However there are specific roles which have emerged within integrated care efforts that we highlight here.

All disciplines of medicine are impacted by integrated care efforts including physician assistants, nurse practitioners and physicians. Primary care providers along with specialty care colleagues learn to work alongside behavioral health colleagues (MA, LPC, LMFT, LCSW, PhD, PsyD) so that they can best introduce, include and incorporate their colleagues and the perspectives they bring to patient care. For this reason integrated care is different than inter-disciplinary care in that medical personnel are asked not just to work with their behavioral health colleagues but also to learn, grow and adapt alongside their partners assuming some overlap in responsibilities and competencies. For example, over time primary care colleagues learn better how to identify behavioral health conditions in their patients and may even learn rudimentary skills in motivational interviewing. Psychiatric professionals, such as psychiatrists, psychiatric nurse practitioners and prescribing psychologists are also key members of the integrated care movement. Their roles vary but often include consultation responsibilities (to other primary care providers) so that their skills with psychiatric medications can be used to support larger portions of the patient population.

Behavioral health providers typically make the biggest adjustments in order to work in integrated care environments. Their task is to assimilate into the medical environment, which requires cultural adaptation in addition to new skill development. For example, BHCs must learn to see patients in briefer time periods and with broader concerns than many therapists are used to in specialty mental health environments. In addition the language and cultural morays of medical environments can seem foreign to new BHCs. All types of mental health licenses work in integrated care settings including medical family therapists, master’s level professionals, social workers, professional counselors, and psychologists. In addition, care managers, who can have a bachelor’s degree, nursing degree or a master’s degree, also play important roles as part of the integrated care team. They typically manage patient registries and provide telephone and in-person support to patients to ensure patients don’t fall through the cracks of follow-up care.

Peer support is one example of community based support that has emerged as part of some integrated care efforts. Peer support counselors are trained consumers of mental health care who come alongside patient to provide emotional and sometimes logistical support to ensure they stick with the plan of care. For example, they may accompany a patient with a mental health condition to a physician appointment and provide some feedback to the office-based care team.

How is it paid for?

An important part of integrated care is the restructuring of payment strategies given that financing often serves to support the structures that regulate and sustain healthcare delivery.

How is it paid for? The short answer to this very complex question is, it depends. Reimbursement for integrated care models is provided by major payers such as Medicare through traditional fee-for-service encounter payments (Psychotherapy codes, Health & Behavior codes), and through newer collaborative care codes. Private payers vary in terms of their support for reimbursement of integrated care models. In addition, local regulations, such as those applied by managed care organizations or state agencies can inhibit the provision of integrated services, such as paying for multiple provider visits on the same day. An additional problem is that these reimbursement strategies are not sufficient to support integrated care models independently given that much of the work that occurs in integrated care is outside of a traditional office visit or face-to-face encounter with a patient. Likely a more suitable solution to payment will arrive in the form of payments that are globally provided to a practice (provided for the care of a certain set of patients) and that are inclusive of medical and behavioral intervention efforts (one payment for all of the care a patient receives regardless of provider). Such payment strategies are being piloted in other areas of medicine by large entities such as Medicare. In the end, payment to the healthcare system needs to be as integrated as delivery of services, providing incentives for providers to work together efficiently and making them and their patient partners accountable for healthcare outcomes.

Find our folder filled with billing advice and resources here.